Salsa for the soul

Chillis may be the key to a good sauce, but there’s more to Mexican cooking than tacos and nachos. Tara Fitzgerald enrols at a home-cooking school in Tlaxcala. Chopping, stirring and mixing, she discovers a fusion of international influences, , receives gratuitous advice about Latin men and discovers a weakness for mariachi. Photography by Fran Gealer

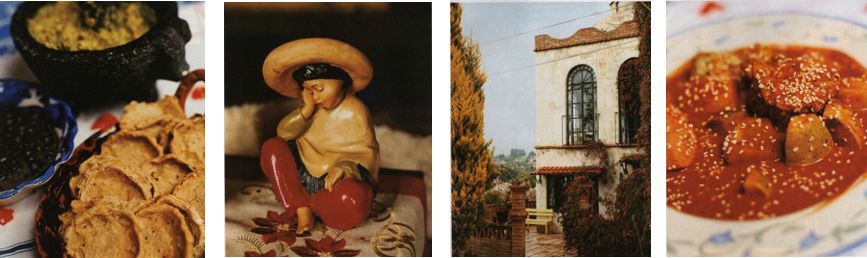

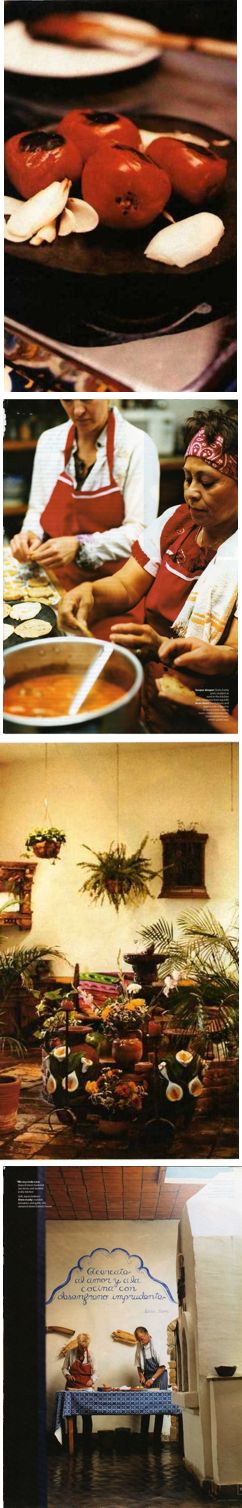

Doña Estela’s kitchen is large, airy and filled with sunshine. Multicoloured talavera tiles decorate the whitewashed walls, and painted over the doorway to the pantry is a quote attributed to the Dalai Lama: “Approach love and cooking with an imprudent lack of restraint.”

I am here to learn to cook traditional Mexican dishes and, to start with, my Californian cooking partner, Troy, and 1 are attempting to stuff a trout with soft cheese and wrap it in hoja santa leaves, and to master the art of making pozole (a spicy soup of pork, chicken and corn), tamales (stuffed, wrapped cornmeal dough) and banana cream pie. Mexican music wafts in from another room, and Estela dances around the kitchen and claps when we accomplish a particularly tricky task.

She keeps getting sidetracked into conversation though. and at the moment she is advising me how to cope with Mexican men: “They need to be kept in line. if necessary with a sharp kick to the backside,” she warns. It is fitting that Estela’s kitchen should be the centrepiece of her comfortable hacienda-style house, because this is where she and her husband run courses in Mexican home cooking. Guests stay with the family and, every morning, Estela Salas Silva and her American husband. Jon Jarvis, teach them the culinary secrets passed down from her grandmother, Doña Eulogia Silva Castillo, who came from the neighbouring city of Puebla. The couple met while Estela was working in her family’s Mexican restaurant in California, where Jon comes from, but they decided to return together to her home which lies five miles from the centre of Tlaxcala, the colourful colonial state capital of Mexico’s smallest state, also called Tlaxcala, a two-hour, 120km drive east of Mexico City.

One of the first things that strikes me about the Mexican Home Cooking School is how you are immediately made to feel part of the family. No one at Jon and Estela’s home stands on ceremony, and their cooking style is hands-on and relaxed: everyone helps with the chopping, stirring and mixing. Guests stay in the family home: my beamed room is painted yellow, has a flagstone floor, a corner fireplace and looks out onto a bougainvillaea-filled garden and a snow-capped volcano beyond. The family dogs are not shy about coming to check out the visitors. And music and chatter fills the house.

Class is meant to start at 10am, which in Mexico is more like 11am. Decked out in red aprons and armed with chopping boards and sharp knives, we — there are never more than six students — prepare our lunch and dinner under Estela and Jon’s guidance, their instructions an enthusiastic mixture of English and Spanish. Estela’s recipes are relatively simple — cheese soup, chicken in red salsa and chiles en nogada (battered, stuffed chillis in walnut sauce traditionally eaten to celebrate Mexican Independence Day)—but require time and attention. Students who have returned home and can’t remember their recipes are welcome to call the couple’s “hotline” for advice.

Mexican cuisine is one of the oldest and most complex, but its reputation has suffered from confusion with the mass-market Tex-Mex fast-food interpretations: burritos, nachos and the like. Estela prefers to concentrate on ancient recipes, passed down through generations of her family, which fuse pre-Hispanic indigenous, Spanish and French traditions.

She started cooking at the age of seven in her family’s restaurant. “All these recipes have been in my head since I was a little girl,” she says. “1 do not teach modern, gastronomic inventions, but rather traditional Mexican home cooking— traditional, wholesome food.” The key to authentic Mexican food, says Estela, is the salsa. “Without your salsa you have nothing.” In the past, women could take days to prepare a salsa, so it pays to know your chillis, which come in an astonishing range of colours, shapes, sizes and degrees of heat.

The mornings pass quickly, and soon it’s time for lunch on the sunny back patio where we enjoy the fruits of our labour and a glass of wine. There are no classes in the afternoon, which gives us time to explore the city of Tlaxcala, the state capital, hike in the pinewoods of La Malinche State Park or just laze in the garden or the surrounding countryside. Wherever you walk there are views of lakes and volcanoes, for the town lies in a valley surrounded by Popocatépetl, Ixtaccihuatl and La Malinche.

On our last night, dinner is late because we forget to switch the oven on, but no one minds as there is entertainment aplenty. We are serenaded by mariachis with guitars by the open fire. Their plangent songs, mostly about the sadness of lost love, plead us to return again — a sentiment that chimes with our melancholy mood at the prospect of having to leave. But then Estela begins to dance, and we open another bottle of wine, and remember that even if we’re going home, we’ll have our new-found culinary skills to remind us of being here. But then Estela begins to dance, and we open another bottle of wine, and remember that even if we’re going home, we’ll have our new-found culinary skills to remind us of being here.

Courses at Mexican Home Cooking cost US$1,200 per person and include classes, meals, transfers and six nights’ accomodation. +52 24646 809 78; www.mexicanhomecooking.com